John S. McFarland, the wonderfully talented author of The Dark Walk Forward (coming December 1 from us), has graced us with a lovely blog post about his lifelong relationship with the creature from Victor Frankenstein's imagination come to life. I think this two-part essay really shows us how literature can become so important to our lives that it can inspire us, no matter where that inspiration lands.

In Part I, John gives us a history of Mrs. Shelley and the time period, and where her ideas might have and did come from.

---

THE DAEMON AND ME (PART I)

If the weather had been better in the year 1816, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley may have never given us this story. That was the year that Mary began work on Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. Most students of climate history will say that something called the Little Ice Age was winding down around taht time, or soon after. That was a period of general cooling of Earth, extending from the end of the Black Death in the 1350s to as late as 1850, by some indicators. Add to this the most devastating volcanic eruption in history, Tambora, in Indonesia the previous year which blocked out and diminished sunlight for months, and 1816 became The Year Without Summer. It was the year Mary and Percy Shelley visited Lord Byron and his house guest, Dr. John Polidori, at Byron's estate in Switzerland.

In her introduction to the 1831 edition of her novel, Mary wrote:

But it proved to be a wet, uncongenial summer, and incessant rain often confined us for days to the house. Some volumes of ghost stories, translated from the German into French, fell into our hands...

"We will each write a ghost story," said Lord Byron; and his proposition was acceded to. There were four of us. The noble author began a tale, a fragment of which he printed at the end of his poem about Mazeppa. Shelly, more apt to embody ideas and sentiments in the radiance of brilliant imagery, and in the music of the most melodious verse that adorns our language, than to invent the machinery of a story, commenced one founded on the experiences of his early life. Poor Polidori had some terrible idea about a skull-headed lady, who was so punished for peeping through a keyhole--what to see, I forget--something very shocking and wrong, of course; but when she was reduced to a worse condition than Tom of Coventry, he did not know what to do with her, and was obliged to dispatch her to the tomb of the Capulets, the only place for which she was fitted. The illustrious poets also, annoyed by the platitude of prose, speedily relinquished their uncongenial task.

I busied myself to think of a story--a story to rival those which had excited us to this task. One which would speak to the mysterious fears of our nature, and awaken thrilling horror--one to make the reader dread to look around, to curdle the blood, and quicken the beatings of the heart. If I did not accomplish these things, my ghost story would be unworthy of its name. I thought and pondered---vainly. I felt that blank incapacity of invention which is the greatest misery of authorship, when dull Nothing replies to our anxious invocations. "Have you thought of a story?" I was asked each morning, and each morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative.

...Many and long were the conversations between Lord Byron and Shelley, to which I was a devout but nearly silent listener. During one of these, various philosophical doctrines were discussed, and among others the nature of the principle of life, and whether there was any probability of its ever being discovered and communicated. They talked of the experiments of Dr. Darwin, (I speak not of what the Doctor really did, or said he did, but, as more to my purpose, but of what was then spoken of as having been done by him,) who preserved a piece of vermicelli in a glass case, till, by some extraordinary means it began to move with voluntary motion. Not thus, after all, would life be given. Perhaps a corpse would be reanimated; galvanism had given token of such things: perhaps the component of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth.

Night waned upon this talk, and even the witching hour had gone by, before we retired to rest. When I placed my head on my pillow, I did not sleep, nor could I be said to think. My imagination, unbidden, possessed and guided me, gifting the successive images that arose in my mind with a vividness for beyond the usual bounds of reverie. I saw--with shut eyes, but acute mental vision--I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine; show the signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavor to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world. His success would terrify the artist; he would rush away from his odious handiwork, horror-stricken. He would hope that, left to itself, the slight spark of life which he had communiated would fade; that this thing which had received such imperfect animation, would subside into dead matter; and he might sleep in the belief that the silence of the grave would quench for ever the transient existence of the hideous corpse which he had looked upon as the cradle of life. He sleeps; but is awakened; he opens his eyes; behold the horrid thing stands at his bedside, opening his curtains, and looking at him with yellow, watery, but speculative eyes.

And so it began.

The end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth was a time of intellectual and philosophical excitement. Scientific investigation and its applications to agriculture, industry, medicine, chemistry, and the structure and direction of society itself were laying the foundation of the modern world. The threshold of a new age was waiting to be crossed. The Industrial Revolution had to be powered. Water, steam and wind were put to ingenious use in new factories and in commerce. Electricity was increasingly understood and seemed to offer untapped possibilities not only as a power source, but as a possible key element and component of the cosmos and even the trigger, or spark of life itself.

In 1780, Luigi Galvani electrified frog legs in his notorious experiment and made them move and twitch. Galvanism was the sensation of Europe and a topic of conversation, according to Mary Shelley, of her husband Percy and Lord Byron. Galvani's nephew, Giovanni Aldini, famously expanded upon his uncle's experiments and electrified an ox carcass, recording a myriad of movement and response.

In 1751, the Murder Act was passed in England. This act made it legal to use the bodies of executed criminals in medical and scientific experiments. The shortage of bodies to use as teaching tools in medical schools was considered an impediment to the advancement of medicine and surgical studies, and an incentive to the blasphemous criminal practice of grave-robbing.

James Jeffray, a popular professor of anatomy at the University of Glasgow, felt the shortage of bodies for dissection and the limitations it presented to his students. Jeffray was falsely accused of being a "Resurrectionist", or grave-robber, and his home was attacked by an angry mob.

Jeffray's student and assistant, Andrew Ure, would eventually put the Murder Act to good use in his research. One evening, Ure arranged for the corpse of newly executed murderer, Matthew Clydesdale, to be delivered to his laboratory. With Jeffray's assistance, as an assembly of the invited curious looked on, Ure began to attach electrodes to the corpse. He then energized the attachments:

Every muscle in his [Clydesdale's] countenance was simultaneously thrown into fearful action; rage, horror, dispair, anguish and ghastly smiles, united their hideous expression in the murderer's face, surpassing far the wildest representations of a Fuseli [artist] or a Kean [actor]. At this period several of the spectators were forced to leave the apartment from terror or sickness, and one gentleman fainted.

The excitement of the possibilities of this new scientific age must have fired Mary's imagination. Another story of a possible influence on Mary is apocryphal, but I would like to think it's true.

It is still said by local inhabitants of Darmstadt, Germany that on their grand tour of Europe, Mary and Percy Shelley took an excursion down the Rhine River, stopping at their town. There, the Shelleys heard the history of the nearby ruin of Castle Frankenstein, and stories of its most famous and notorious inhabitant, a necromancer, metaphysician, alchemist, and possible body snatcher named Johann Konrad Dippel.

Dippel had been born in the castle in 1673, which by then was an ancient structure that had fallen into disrepair since the time of the Reformation. Fired by a wide range of interests, both scientific and theological, Dippel gained praise early in his career, from Swedenborg, who later changed his opinion and called the German one of the evilest men on Earth. Developing what he claimed was an elixier of eternal life, Dippel tried to exchange the formula for the mixture for title to the castle of his birth. This failed, and after being rumored to be using human corpses in his experiments, Dippel was literally run out of town by outraged villagers.

If Mary actually heard these stories as many allege, they would have been an irresistible influence on her, and tremendous source material to have been stored in her subconscious.

One further connection between the creation of the novel and Mary's influences: John Polidori, the fourth member of the party who spent the Year Without Summer with Lord Byron, and who participated in the ghost story competition. It was he who created the tale of the skull-headed lady that Mary thought was so forgettable.

In 1821, three years after the publication of Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus, Polidori committed suicide by taking prussic acid (cyanide), which had been developed a century or so earlier in Berlin by Johan Diesbach, from potash he had acquired from Johan Konrad Dippel.

~ John S. McFarland

---

In Part II, John will explore his own connection to the Frankenstein story and why it means so very much to him.

by Laura Chouette on Unsplash

From Wikimedia Commons: "Richard Rothwell's portrait of Shelley was shown at the Royal Academy in 1840, accompanied by lines from Percy Shelley's poem 'The Revolt of Islam' calling her "a child of love and light."

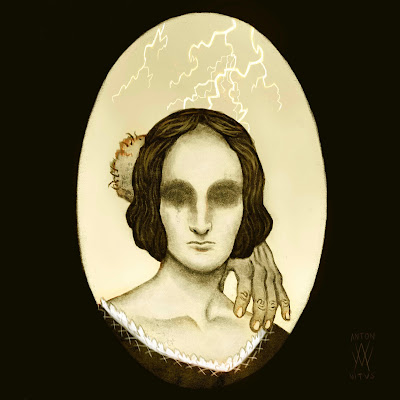

Mary Shelley by Anton Vitus Westerlund from ArtStation

An etching representing Dr. Ure's galvanism of the corpse of Matthew Clydesdale. From Wikimedia Commons: "Figure 33, an illustration labeled 'Le docteur Ure galvanisant le corps de l'assassin Clydesdale' from Les merveilles de la science, ou Description populaire des inventions modernes, 1867, by Louis Figuier"

Image by lapping on Pixabay.

Image by Deniss Ignatjev on Pixabay.

Comments

Post a Comment